Update 2/9/16: This content was selected for Digital Humanities Now by Editor-in-Chief Ben Schneider based on nominations by Editors-at-Large Harika Kottakota, Heriberto Sierra, Marisha Caswell, Vanessa Raymond, and Laura Vianello

See also Miriam Posner’s talk from this day: “Money and Time.”

See also Scott Kleinman’s talk from this day: “Digital Humanities Projects with Small and Unusual Data: Some Experiences from the Trenches.”

Thank you to Peter Krapp and The Humanities Commons and Data Science Initiative for the invitation to speak today along with all of my esteemed colleagues. Everyone here represents a slightly different facet of Digital Humanities. It should make for a very interesting day!

Thank you to Peter Krapp and The Humanities Commons and Data Science Initiative for the invitation to speak today along with all of my esteemed colleagues. Everyone here represents a slightly different facet of Digital Humanities. It should make for a very interesting day!

Instead of discussing results today, I’m here to talk about the messiness of the inner-workings behind a small Digital Humanities project and issues inherent to data. I guess I’m also a tale of how to do Digital Humanities with the least possible institutional support in a field that continues to diversify and evolve intellectually and institutionally.

[About 20 minutes before the day began, Peter recommended that I outline the boundaries of Digital Humanities for this audience. The slides below offer that overview, but we can also add Alan Liu’s Map of Digital Humanities (Prezi or downloadable PPT — PPT is more recent). I didn’t quite get to the last 2 pp of this talk with this new addition of DH context. During the Q&A, more came out about how much is yet to be done with my DH project and the intersection with pedagogy. Ultimately, my DH project focuses on new developments in DH as the tools become easier to handle.]

- This is my version of DH – a mix of material & digital

- The debate about what is DH

- But it’s been calcified somewhat with a Wikipedia entry – a good starting point

- My evolution as a DHer from Day of DH

- An explanation for DH in English Departments

- In 2006, the requirements for DH. Has it evolved?

- DH is a database of literary materials

- DH is TEI to mark up a literary text

- DH is maps!

- DH is spectral imaging to restore manuscripts

- DH is archival materials that build on other’s work

What began as a digital scholarly edition, Forget Me Not Hypertextual Archive (2005), focusing on recovering and revealing an early nineteenth-century publication, turned into a traditional scholarly monograph, Forget Me Not: The Rise of the British Literary Annual 1823-1835 (2015). Both the monograph and digital scholarly archive reveal the multi-vocal and hyper-feminized literary annual’s interaction with print culture and the production of literary materials and material objects throughout the nineteenth-century. The literary annual, some 300 titles published 1823-1860 in England with nationalistic derivations produced in France, Germany, America, and South America, became the locus of authorship to almost every canonical and non-canonical author, poet, and artist in England and America. The best-selling titles were published for 25 years and enjoyed a healthy readership distributed across class, gender, and geographical audiences. However, the annuals themselves have previously been unavailable for study because most libraries and archives discarded them as unimportant, popular culture during an age when the mechanization of print encouraged distribution of massive amounts of reading materials. The digital archive, edition of gothic short stories, and monograph are all meant to the absence of scholarship on this wildly popular literary publication. First, a little background on this literary form before delving into the DH aspect.

Introducing the Literary Annuals

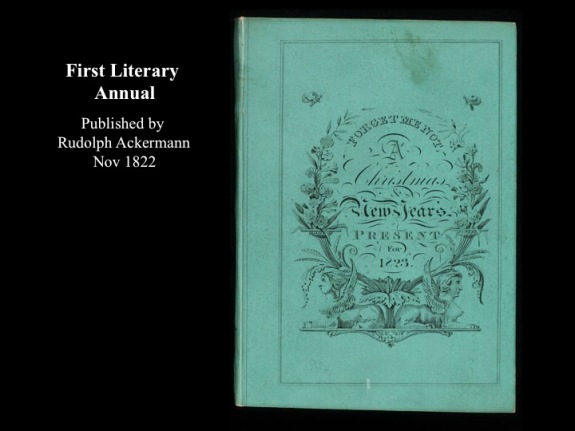

Inspired by intercontinental literary forms and created by a successful art publisher, Rudoloph Ackermann, the literary annual first appeared in London in 1822 and was claimed by a myriad of publishers to represent the best of British ingenuity – even though the material form, the printing process and the editorial methods were really borrowed from French and German pocket-books, albums, and emblems. Originally, literary annuals were to replace the conduct books of the late 18th Century, but the editors’ and publishers’ claims don’t match that intention.

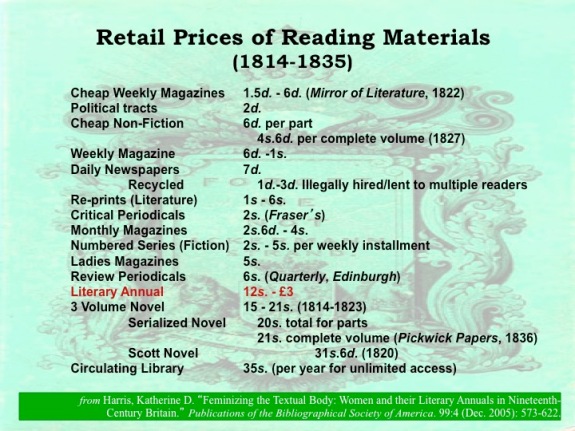

By wrapping beauty, literature, landscape art, and portraits into an alluring package, for 12 shillings editors and publishers filled the 1820s with this popular and best-selling genre.

By wrapping beauty, literature, landscape art, and portraits into an alluring package, for 12 shillings editors and publishers filled the 1820s with this popular and best-selling genre.

Originally published in paper boards, the annuals were usually whisked away to be re-bound in beautiful leather covers.

Originally published in paper boards, the annuals were usually whisked away to be re-bound in beautiful leather covers.

By 1828, publishers employed the latest innovations in binding and switched to silk to amplify the value of the material object.

By 1828, publishers employed the latest innovations in binding and switched to silk to amplify the value of the material object.

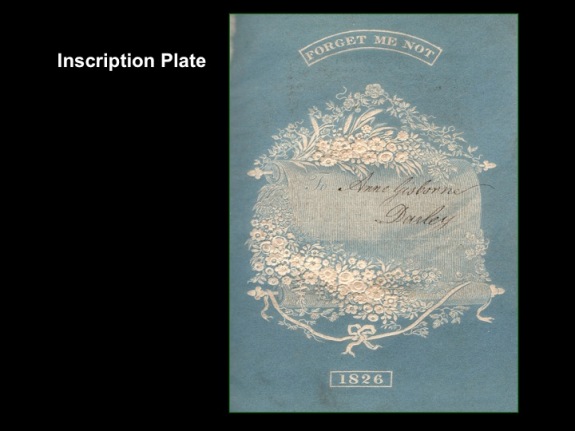

Each annual typically offered a confined space for dedication.

Each annual typically offered a confined space for dedication.

Early annuals offered practical information similar to the Stationer’s Company’s almanac. But that would soon disappear in favor of more literary and visual content.

Early annuals offered practical information similar to the Stationer’s Company’s almanac. But that would soon disappear in favor of more literary and visual content.

Engravings were cast from popular landscape and portrait paintings (including many by J.M.W. Turner) but rarely garnered fame for the engraver who was deemed a mere copyist and denied entrance into the Royal Academy.

Engravings were cast from popular landscape and portrait paintings (including many by J.M.W. Turner) but rarely garnered fame for the engraver who was deemed a mere copyist and denied entrance into the Royal Academy.

Often engravings were commissioned like this one.

Often engravings were commissioned like this one.

…and then well-known poets were asked to render an accompanying poem, the worst kind of ekphrasis: work for hire – eventually much to the poet’s dismay. But let me stress this: EVERYONE contributed to the annuals, even if they despised the genre.

…and then well-known poets were asked to render an accompanying poem, the worst kind of ekphrasis: work for hire – eventually much to the poet’s dismay. But let me stress this: EVERYONE contributed to the annuals, even if they despised the genre.

At first, reviewers enjoyed the annuals, offering long excerpts and recommending particular annuals to their readers. Within 5 years, though, reviewers began to write with disgust about the genre – primarily with objections to the poetess aesthetic.

At first reviewers praised annuals as possessing “a tone of romance, which, set off as it has been by poetry of a very high order, can have no other possible tendency than to purify the imagination and the heart” (Nov. 1826 Monthly Review 274).

With a large audience almost immediately clamoring for more literary annuals, Ackermann and his editor, Frederic Shoberl, created a second Forget Me Not for 1824 and found themselves competing with Friendship’s Offering and The Graces. By 1828, 15 English literary annual titles had joined the market only to vie for an audience against 30 more titles by 1830.

Usually containing a mix of short stories, poetry, historical accounts, and other types of writing, the literary annuals boasted 20-30 original compositions with each publication. Of course, Rudolph Ackermann and other publishers capitalized on the most popular literary forms of the moment. Of course, the gothic novel was outselling any single author volume of poetry at such a high rate that publishers were declining new poetry manuscripts by the likes of Keats, Coleridge, or Percy Shelley in favor of producing volumes of Sir Walter Scott’s best-selling historical romance and Gothic novels. By this virtue of popularity, the annuals, so I hypothesized, must too have capitalized on this trend, especially after the wildly popular first edition of Frankenstein published in 1818 and then revised for the 1831 second edition. I set out to figure this out – by counting, at first.

Annuals & the Gothic

I chose to limit my study of gothic short stories in literary annuals to 1823-1831 because in 1831 not only did Mary Shelley publish the 2nd edition of her popular novel, Frankenstein with its famous introduction, but the literary annual craze had reached its peak, with titles such as The Keepsake, Literary Souvenir, Friendship’s Offering and, finally, the Forget Me Not. Because parody is usually the marker of solidifying (and then moving beyond) a literary tradition, 1830 marked the year that the literary annual genre was solidified with Thomas Hood’s parody, The Comic Annual.

By 1818, though, the Gothic tradition had already transformed itself away from the High Gothicism of Mrs. Radcliffe and Matthew Lewis’ novels because of Sir Walter Scott’s re-working of the genre in his historical romances away from simply horrifying and terrifying its innocent readers.

Critiqued as leading to false notions of reality, the Gothic novel was thought to over-excite young women and mislead them to think that life was as romantic and suspenseful as any Gothic novel. According to close readings of the genre, beginning in 1818, the “New Gothic” tradition cements itself as the latest type of Gothicism, as is suggested by Robert B. Heilman: “novels that turned from old forms of external terror to ‘an intensification of feeling’” (Alexander 409).

According to Robert Mayo, by 1810, the Gothic short story was well-established as fiction (448) and came in the form of Gothic Romance, Historical Romance, Sensational Fiction and Sentimental Horror. They were published in Blackwood’s and London Magazine, as well as the Lady’s Magazine and Lady’s Monthly Museum even prior to 1800. Between 1790 and 1820, Mayo describes the Gothic short story – usually only 2500 words or less to fit magazine page limitations, differing in its “machinery of terror” (454) and fragmentary at best. However, the Gothic short story was well-adapted to the magazine because “their moral tone accorded well with the didactic claims of the miscellanies . . . and no matter how desperate the pressure of events, found room for a moral” (“Gothic Romance in the Magazines” 765). Mayo claims that the Gothic short story then fell out of favor by the 1820s.

After reading through 90 short stories in the most popular and best-selling literary annuals, I found that the stores contain the supernatural excitement of early Gothic novels. However, the conclusions to these short stories were often more appropriate for the literary annual and the young minds’ of the readers – they were disappointingly didactic or explained away through circumstance, which makes them more Mrs. Radcliffe than Monk Lewis – a penchant for “natural terror” rather than the supernatural.

These stories, then, signal this shift in the Gothic tradition, from an old to a new intensity of feeling that was localized in a familiar setting, much the same as later novels such as Dracula, The Woman in White and Wuthering Heights. With this, the literary annuals act as catalysts (along with many other periodicals) for this evolution in literary tradition – even despite the disdain from critics and literati. But this is from a scholarly close reading – of 90 short stories. Though I kept track of notes in assessing these writings, it’s almost impossible to authoritatively assess these literary moves across the entire swath of literary annuals. So, I turned to counting in the most rudimentary ways using Google spreadsheets and the analysis tools available for visualizing the data.

Assessing Gothic in these Annuals

- 96 gothic short stories published in 28 volumes totaled approximately 1,554 pages 1823-1831.

- In some years, a literary annual might dedicate 30% of its 300 pages to Gothic short stories, while in other years there were only 5%.

The Forget Me Not maintained an editorial consistency with Frederic Shoberl managing the annual until its demise in 1847. Alaric A. Watts founded and controlled The Literary Souvenir, previously The Graces in 1824, until it became the Cabinet of Modern Poetry in 1836. Charles Heath, an engraver and founder of the most popular and successful literary annual, The Keepsake, selected first, accomplished Gothic novel writer, William Harrison Ainsworth, then Frederic Mansel Reynolds as his editors. Letitia Elizabeth Landon and the Countess of Blessington briefly edited this annual and Heath’s Book of Beauty after 1831. Friendship’s Offering has, perhaps, the most mysterious beginnings and editorship: Thomas K. Hervey, Charles Knight, and Thomas Pringle each edited volumes through 1831. With the exception of William Harrison Ainsworth, none of the editors contributed Gothic short stories to the annuals represented in this collection, though they did contribute poems to various volumes. Ainsworth contributed to all but the Forget Me Not. The editorial voice here is key.

Though the Forget Me Not was not the most popular literary annual by 1831, after 9 volumes, and led by Frederic Shoberl and Rudolph Ackerman’s business acumen, the Forget Me Not publishes by far the most Gothic short stories of these four literary annuals.

An Accounting

Beginning with a single, 21-page Gothic short story in the 1823 volume, the Forget Me Not incorporates 8 stories, totaling135 pages and representing 35% of the 1826 content. In 1830, the Forget Me Not again approaches 30% of their content dedicated to Gothic short stories, totaling 10 in number and 125 pages. The Forget Me Not 1828-1830 published over 400 pages of content, equaled only by The Literary Souvenir’s overall pages for 1826-1828. The more popular Keepsake maintained under 300 pages of content 1828-1831 but included four Gothic short stories over 109 pages in 1829, which is represented as 30% of the content. Friendship’s Offering’s contents range anywhere from 222 to 418 pages but consistently contains the lowest number of Gothic short stories. Alaric Watts’ Literary Souvenir was the Forget Me Not’s greatest competitor for number of Gothic short stories and number of pages dedicated to these stories. By 1829, the popularity of the Gothic short story is apparent: the Keepsake, Forget Me Not, and Literary Souvenir each dedicated 30% of their content to Gothic short stories.

In total, the Forget Me Not includes 50 Gothic short stories and 768 pages over nine years; The Literary Souvenir includes 28 Gothic short stories and 441 pages over seven years; and The Keepsake includes 10 Gothic short stories and 215 pages over 4 years. In comparison to the total number of pages produced overall by each literary annual title, the Forget Me Not reserves 21% of its pages for Gothic short stories against The Literary Souvenir’s 16.4% and The Keepsake’s 15.9%. In total, the forthcoming collection of transcriptions contains 96 stories and 25 engravings from 28 volumes of literary annuals. In case all of those numbers were too boggling to keep up with, let me show you something really groovy:

From 12 to 19 engravings were included in each of these literary annuals. Charles Heath, a well-known engraver, was adamant that The Keepsake would offer a higher number of engravings than any other annual. The Keepsake, however, leads with 8 engravings accompanying all of its Gothic short stories 1828-1831, something that the other annuals did not do. In fact, The Keepsake for 1830 includes 2 engravings with Mary Shelley’s story, “The Mourner.” The Forget Me Not, over 9 years, includes only 7 engravings to accompany its stories.

As you can see by the engravings here, they don’t necessarily scream GOTHIC. In fact, many of the engravings maintain a tone or topic according to the literary annual title: the Forget Me Not seems to focus on bucolic scenes while The Keepsake employs the horror-stricken scene or that sublime awe-fulness so redolent of Gothicism.

New Project: More than an Accounting

Having now established the undeniable impact of the literary annual on British, American, French, German, and Spanish print, literary, and art culture, my work turns towards topic modeling with MALLET and comparing corpora with Voyant to study several queries concerning over 600 literary annuals (each with 30-40 literary works and 10-20 engravings). The project begins with a small sampling by comparing 90 Gothic short stories published in literary annuals 1823-1831 (from Gothic Short Stories in British Literary Annuals [2012]) to those short stories published in other venues using corpora recently created with Ted Underwood and Franco Moretti’s distance reading and topic modeling projects (corpora that are now freely available as transcripts). With a corpora of more than 90 short stories 1823-1831 published prior to the publication of the second edition of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, if I can answer some of the below questions, then I will be able to articulate (definitively) if the literary annual genre actually changed the gothic short story and hence altered the most popular literary genre on many continents in the nineteenth century:

- Do the engravings mirror the gothic-ness of each short story? Why or why not?

- Is the topic of each engraving representative of each literary annual’s overall tone?

- Are there differences in the types of short stories each literary annual published?

- Why the dip in percentage of pages dedicated to Gothic short stories?

- Why does the Friendship’s Offering have the lowest number of Gothic short stories?

- Who is the hero/heroine in these stories across all 4 titles (man? Woman?)

- Are the stories set in foreign lands?

- What is the role of women in these stories?

- Do male authors construct stories differently from female authors?

- How do these short stories compare to Gothic novels?

Both Ted Underwood and Andrew Piper gave thrilling papers at the MLA this January that highlight use of a large corpus to run several hypotheses. Ted discussed the instability of gender 1780-1900 in fiction while Andrew assessed the development of character across novels. And Deirdre Lynch responded with a reminder not to leave close reading too far behind because there are inherent risks to consider with genre studies.

Both Ted Underwood and Andrew Piper gave thrilling papers at the MLA this January that highlight use of a large corpus to run several hypotheses. Ted discussed the instability of gender 1780-1900 in fiction while Andrew assessed the development of character across novels. And Deirdre Lynch responded with a reminder not to leave close reading too far behind because there are inherent risks to consider with genre studies.

With these types of studies, along with Stanford’s LitLab and the initiatives at UC Berkeley, there’s a chance for an individual scholar to tackle new forms of literary inquiry.

Using a corpus for comparative studies provides a wonderful depth to the development of Gothic short stories. However, the history of literary annuals and their meddling editors complicates the fact that literary voice was sometimes strongly shaped by editorial intervention. Frederic Shoberl kept his hands off of his author’s work, as far as I know. However, others freely re-wrote or altogether replaced literary submissions but retained the original author’s name. So, too, are issues of anonymity. Mary Shelley declared that her best work was in short stories written for annuals, but the scholarly community has recently (in the last 10 years) identified some of her unattributed short stories. In a final act of commodifying the literary annual, some editors placed famous author’s names on works that these authors didn’t author solely for the purpose of selling literary annuals. Remember, at first, literary annuals’ table of contents didn’t identify all of their authors. In fact, anonymity was the norm. With the first two years of success, however, authorship became overwhelming commodified in literary annuals, a practice that reflected Britain’s export of their literary genius as evidence of the British Empire and its cultural dominance. In “Networking Feminist Literary History,” Susan Brown highlights this dilemma – how do we marry close reading, literary history, and distant reading?And, how do we escape those silences and gaps in a corpus that replicates the traditional literary canon? More shades of a long ago post, “Big Data, DH, Gender: Silence in the Archives?” with Miriam Posner, Jacqueline Wernimont, Ted Underwood, and Roger Whitson.

So what do we do now? The literary annual is a particular genre and literary form that is nearly impossible for a single scholar to read and assess. With more than 600 annuals and 30-40 literary writings in each, not to mention the visual representation of art, any one person reading through a mythical collection or archive of annuals would need a monumental amount of memory. Most scholars have made their way into literary annuals through a single author because that’s a reasonable bite-sized amount of material. There’s also the issue of finding a complete physical collection as opposed to microfilm. University of South Carolina, the NYPL, and the British Library own a wide swath of British annuals, but not enough to make assessments across the entire genre. I amassed a collection of 300 literary annuals in a personal collection that is geared towards assessment of the most popular annuals 1823-1860.

What tools will I use to achieve this? Much of my work, even with the Forget Me Not Archive back in 2005, relied on open source tools or relatively inexpensive equipment, such as a desktop scanner and digital camera. Though some portions of that scholarly edition were rendered into the acceptable coding (TEI and appropriate metadata) by The Poetess Archive, there’s no real place for it now. I mean, it’s not even searchable and it still lives in frames authored with MS Frontpage. Regardless of the outward-facing tech, the images were rendered in archival-quality recommendations as TIFF files at the appropriate resolution, and the information gathered about each volume represents the beginnings of a scholarly edition according to parameters of scholarly editions in 2002. Since that time, requirements for digital scholarly editions have evolved but not necessarily normalized. The Archive, the only of its kind on literary annuals, erases the physical book and all of the important information necessary to assess publishing culture in early 19th century England — but this is not new; it’s an issue stemming from the use of microfilm and even Google Books to assess more than the letters on a page.

The project isn’t big enough to gain the attention of an NEH DH grant. Instead, I turn to bibliographic, book history, and textual studies scholarly organizations for grant funding. In my institution, including students in a project will get on average a $5,000, $2500, or $4000 grant. Because some of the tools are now out of the box, such as Scott Kleinman’s Lexos, or Voyant and because Stanford’s LitLab, which is down Highway 101 from San Jose State, generously allows me to sit it on presentations, teaching myself some of the technological aspects of this research is well within my grasp. Alan Liu, like others, created DH toychest with tutorials to help his students access these kinds of DH projects — but the toolchest works well for my small-ish project as well.

But what would this project look like if it were at one of the universities where Digital Humanities is institutionally supported? University of Illinois, Stanford, University of Nebraska, McGill, Texas A&M, University of Victoria, UC Berkeley? As a DH scholar, I need a lab. Not the type necessarily that scientists require with start-up funds. I need a space to meet with other scholars who are also interested in this type of exploration. I need access to a very large, privately owned corpus. And, because much of Digital Humanities relies upon collaboration, I need access to local colleagues for discussions. Those models exist. Stanford’s LitLab is one of them. What’s happening at UC Berkely is another. Without that infrastructure, the regular meetings, projects like mine are orphaned until I carve out time to work on them or wrangle a good-natured colleague into answering some questions or even coming on board. And this new type of DH project that I’d like to grapple with engages with DH very differently than my original digital archive. It’s an attempt to assess the rise of the short story in a narrowly defined hypothesis. I may turn out to be wrong in a few of my queries, but no doubt that the work, once the comparative corpus has been obtained, can render some very interesting findings without necessarily reading through 25 years of short stories published in England by all sorts of authors. My project unintentionally (or maybe it’s leftover from my original charge as a doctoral candidate to say something new) works toward exposing the richness of the literary annual’s contents. It does continue in a feminist recovery project, however. It doesn’t resolve the access problem or the canonical validity reputation of the annuals and their authors. That was the original impetus of my digital archive — a lofty dream of my naivetee.

But, I speak of only one kind of Digital Humanities project. The experienced set of speakers gathered today represent DH with a variety of institutional purpose and focus. I look forward to pilfering data, tools, and techniques from their talks for the rest of the day. Thank you.

Thanks for the photos from pals in the audience: Kathi Inman Berens, Miriam Posner, Peter Krapp, and Jeremy Douglass.

References:

-

Ted Underwood & David Bamman, “The Instability of Gender,” MLA 2016 presentation

-

Andrew Piper, “The Constraints of Character. Introducing a Character Feature-Space Tool,” MLA 2016 presentation

-

Mark Algee-Hewitt’s presentations at MLA 2016 and at Stanford LitLab

-

Susan Brown, “Networking Feminist Literary History: Recovering Eliza Meteyard’s Web.” Virtual Victorians: Networks, Connections, Technologies. Palgrave 2015

-

Alan Liu, like others, created DH toychest with tutorials to help his students access these kinds of DH projects — but the toolchest works well for my small-ish project as well

-

Ted Underwood’s primer “Topic Modeling Made Just Simple Enough”

-

Matthew Jockers MacroAnalysis: Digital Methods & Literary History. U Illinois Press, 2013

4 comments

Do you want to comment?

Comments RSS and TrackBack URI

Trackbacks